HOME

Transeuropa

Transpoetry Project

Daniel Göske

Workshop

Anant Kumar

Workshop

Poetry

Under Pressure

moire

kabinet

Transpoetry

A program run by Professor Alexis Nouss

Cardiff University School of European Languages, Translation and Politics.

a collaboration with

Artist Glenn Davidson Digital Interaction Design,

Moire Framework and Site

The site documents the following

teaching and public events:

Transeuropa Transpoetry Project

Collaborations with Artstation,

Philip Gross and Tsead Bruinja at

Chapter Art Centre Cardiff.

May 2011

Daniel Goeske workshop

Workshop on translation of Derek Walcott's The Prodigal.

Anant Kumar workshop

Workshop on translation of A. Kumar's poems

Poetry under Pressure

May 2012

<

>

1 - 48

Philip Gross and Tsead Bruinja and Glenn Davidson at TransEuropa Festival Cardiff with the participation of the Cardiff School of European Studies)

Saturday 7th May, 18:00

Chapter Arts Centre, Market Road, Canton, CF5 1QE

The Project

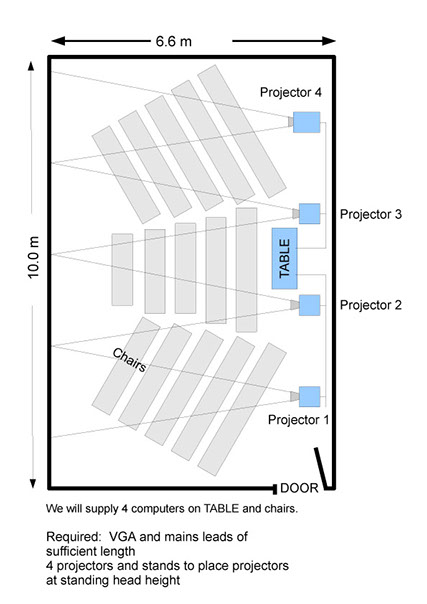

Part A : A framework, devised by Glenn and Alexis for the exchange of poetry, written whilst in motion crossing Europe, ideas and impressions of the train journey were to colour and influence the process of creative writing. This involved inviting two outstanding poets, Philip Gross and Tsead Bruinji, on mirror journeys to visit one another's home cities. Each was to write a poem and present it in Cardiff for further investigation.

Part B: A workshop, the poems are being translated into more than 10 languages, an act of displacement... a term which refers to the root of the word translation. So poems in transit are further translated into many languages. This conceptual ground is a meditation on Europe's cultural migration and the global Diaspora.

Real-time translation

Students and staff have used mobile phones to instantly publish their textual throughts, using the artists TXT2 software. A line, "I am out of my languages", taken from Philips poem Spoor, formed a short provocation which was texted and projected onto a screen for all to read. The room burst into activity, and within around four minutes a series of translated versions emerged, line by line below the first. Witnessing this was a fascinating experience, for the first time those present witnessed something of the nature/nurture conflict within the term translation. These short pieces of projected text turned out not to be copies at all, but completely new, and therefore displaced, originals! See the banner on the right

The Chapter TXTEU event

Poems, poets, translators, media projection and live txting will provide an array of engagement. The poets will read, the translators present their new translated originals. The Poets will use the txting system to write a Heiku (a short poem) which the translators will translate, before the floor was opened up to everyone to join in.

Background to the Artists

Philip Gross, who was awarded T.S.Eliot award for 2009, was introduced to this project by Glenn, they met through a poetry film project in 2010. Philips father reached Britain from Estonia in 1946 as, officially, a Displaced Person. Philip is currently writing about him in a new book, which is entirely about the travelling, the being in motion, of his father's displacement...And so a travelling poetry proposal appealed and the outcome, the poem Spoor, exposes glimpses of his father's life in reflections of himself, within a universal frame of rail tracks and landscape (matter) and continuum (time).

Tsead Bruinja, is short listed to be Amsterdam's poet laureate, he was bought into the project through the TransEuropa Festival. We are more than happy to be working together. Tsead's work immediately resonates with place, with family and life cycle, his poem Bed & Grave forming this project is grounded in a notion of the well known or fond journey.

Glenn Davidson recieved the Beacon for Wales award to develop TXT2, exploring the creative and social aspects of text messaging through a public practice of site specific TXT2 installations. These engage with a wide range of social enclaves, places, organisations and issues. Within the story of TXT2 was the story of the Creative Texter - see www.artstation.org.uk/EM10_C_Davidson.pdf exploring how people can use phones in creative ways In 2010 the artists produced a crowd sourced poetry event -TXT2Baylit created for the Baylit Literature Festival . (www.artstation.org.uk/BAylit).

Glenn is a Fine Artist he co directs Artstation with fellow Artist Anne Hayes, undertaking Art Installation, media and film, Interaction Design, production and cultural consultancy.

More information www.artstation.org.uk

Spoor

1.

Doctor doctor

it’s the way things pour

on round me when I shut my eyes

like the glassy but shuddering pause

at the lip of the weir.

It’s either that or

it’s the stasis of speed,

the way the furthest tree keeps pace

unmoving, while what’s near

(tell me: is this a sign

of ageing? or the age?)

twitches past in a blur.

2.

Or now: I’m in the dark

of tunnel vision.

How much of the journey will be

in non-space, new space

borrowed from the earth or sea

or from the air above a valley?

Here’s a flicker, in the long

view, of a granite viaduct’s brief

being-there-ness — and me

one pulse in that flicker. Crack

an atom, track its scattered spores

of particles; you have to choose

which to grasp: mass or velocity.

Is that the bargain, then: the more

we’re everywhere,

the less substantial we will be?

3.

Or now: looking down into gardens,

which could be yours

or anyone’s, though more likely

the poor…

Their bedrooms even, each unguarded

detail magnified

like mist-intricate rockpool weed.

(The child

I was reached in to touch, and missed

as my arm became crooked, the hand

not quite mine;

it could have turned to me

and beckoned;

it had crossed the line.)

4.

Faced backwards, I’m ready to fall

into my destination unforewarned

except there’s this shadow, not unlike my own

thrown by its, no, by many lights

behind me, into fragments, a diaspora,

displacements, which however come in, on

and clearer if I step towards them,

draw them closer to the vanishing point

where they will, no, we will, be one.

5.

As in the station washroom,

my reflection in grey polished steel,

the see-and-see-through self

advancing in the automatic door

before the stomach-punch thud

and wheeze of opening… or

like the shape of my father

through the falling-water blur

of his shattered languages; who

was the man I saw yesterday

shuffling towards me, head

shaved as if for delousing,

on the (tactfully) locked ward?

6.

Now I’m out of my languages (English,

French) and on the crowded

InterCity through Den Haag,

the shape of space around me changed,

between me and the next man, and

the next, by the lack of one casual word

we might share; it recalls me

to the cramped airless world of the shy

… or to him, in his word-naked

world, as tight as a lift cage,

strangers pressing in too close

and some of them in uniform

… or to any illegal, without papers,

the air sweating against him,

every breath a risk. Do not meet

word with word, or eye with eye.

7.

Of course things pour.

You want a different planet?

Right now, we’re sitting here faster

than the speed of sound.

The wonder is that we can talk,

I mean, converse, at all.

8.

Did I think I was going to meet him

half way — after-image at least,

the inside-out of what his converse

journey must have printed on his eye,

all his kind, coming out of the east /

west rip of Europe (1946,

that was, already hardening

like a bad scar)

truck-loaded through wrecked

Rhinelands, fallen sky

for miles in flood-fields

where the dykes were breached

— Europe After The Rain

as in Ernst’s wax-rubbing, not

of a plaque or tomb but the hide

of one predator reptile or other

that had thrashed and gored and

thrashed before they (he

could never quite believe it)

died?

9.

Where

in his brain

between the dried

blood shadow

of stroke damage,

doctor

doctor, are

the traces?

Scuff marks

in the dust.

A stray print in the mud.

Where can I track

(I find a word

in Dutch now on the station

indicator board

for track as in railway,

for these lines)

his spoor?

Philip Gross : Cardiff - Amsterdam 03.04.11

Tsead Bruinja : Amsterdam - Cardiff 04.04.11

bed

the names you use

for food cutlery and service on the table

are not the first names

which I learnt for food cutlery and service

and when you touch me you sometimes touch

a completely different part of me

than where my sister

would pinch me after I'd teased her

or where my mother would put a little

more effort in washing me

we sleep in the same bed

but yours is shorter

and mine sounds more

like the bleating of a goat

your father and mother

your grandfathers and mothers

they are called something else

they never cuddled up to you

gave you a kiss

or a good wash

we live in the same world

I cuddle up to you

give you a kiss

for those things we use

the same names no

your bed and kisses

are growing longer

every year

grave

I know where my stuff

and money will go

when I die

but nowhere

have I written down

that I want to enter the earth

naked in a blanket

where doesn't matter to me

my mother wanted to be far away from her children

because we had to move on

according to her

she was buried

next to her father's father

granddad went over there almost

every day

my granddad and grandmother lie neatly together

beside the church they didn't believe in

next to their home

where granddad would peel an apple for her

and change the channels with a bamboo fishing rod

we never watched a channel for more than one second

all three of them aren’t lying in the ground

which they were born on top of but never a lot further

than 20 miles from it

from where I live

you can’t see their graves

or find one on a day’s walking distance

leeuwarden furthermore

is further removed from amsterdam

than the other way around

and I just realized that I am already somewhere else

I dropped skin and hair in indonesia zimbabwe

and nicaragua

urinated and ate in their restaurants

the body renews itself

no part of you is the same at the end

and when it will die that will also be the end of my soul

so returning the empty corpse would serve no purpose

where you’re going to leave it doesn’t really matter to me

but you know that I want it to enter the earth

in a blanket naked

and in case you’ve accidentally

become a believer again around that time

throw before the sods

fall on the bones I left behind

a bamboo fishing rod

in with them

Glenn Davidson : TXT2EU

We are out of our languages - The Second Original

From the first workshop

Translation is a kind of impossibility especially in the context of a poem

Below: TXT2 transmissions by students during Glenn Davidson's lecture for the School to European Studies / Translation Studies 6th April 2010.

A new autopoietic work of second originals, based around a short extract of Spoor by Philip Gross from his commissioned poem for TransEuropa Festival - a travelling poem

From Spoor...

"i am out of my languages"

i am out of my language...

Je suis hors de ma langue

Estoy fuera de mi idioma

Eimai ektos tis glwssas mou.

i'm out of my depth?

Je ne parle pas ma langue

I have lost my identity

sono fuori della mia lingua

Mo ti kuro lede mi

je suis dehors de ma langue...

Estoy ajena a mi misma

I am out of tongue

dwi ar goll!!!

I'm don't speak proper English butt innit?...(Welsh valley dialect)

Me encuentra ajena a mis origines

Ana la agder atklm alloga (arabic)

time:

# 15:53:53

# 15:55:00

# 15:55:25

# 17:55:38

# 15:55:41

# 15:55:51

# 15:55:57

# 15:56:10

# 15:56:15

# 15:56:20

# 15:56:22

# 15:56:23

# 15:56:24

# 15:56:53

# 15:58:48

# 15:59:03

Arabic

نظرة الى الوراء, انا جاهز للسقوط

الى غايتي بدون حذر

الا ان هناك هذا الظل, ولكنه لا يختلف عن

ما هو ممدد لي, لا, من العديد من الاضواء

من خلفي, ينتشر الى شظايا و الى الشتات,

النزوح, والتي مع ذلك تأتي,

بوضوح أكثر أذا خطوت خطوة اتجاههم,

تسحبهم اقرب الى نقطة التلاشي

حيث أنهم سوف, لا, ونحن سوف, نكون واحد.

5

من خلال الباب ذاتي الحركة

وقبل ان يجلجل صوت اللكمة على المعدة

وصوت ازيز فتح ال ..... أو

مثل شكل مظهر والدي من

خلال ضبابية تساقط المياه

أنه صاحب اللغات المحطمة؛ من

كان ذلك الرجل الذي رايته بالامس

يجر رجليه اتجاهي, حليق

الرأس كما لوكان محجوز( بلباقة) في جناح مغلق

من اجل التخلص من القمل؟

Spoor by Philip Gross (stanzas 4-7)

Translated into Arabic by Sadi Elsassi

4

6

الآن ان خارج نطاق لغاتي ( الانجليزية,

الفرنسية) وعلى طريق المزدحم بين المدن الذي يمر خلال دن هاخ ( مدينة لاهاي)

تغير شكل المكان من حولي,

بيني وبين الرجل التالي, و

ثم التالي, بسبب عدم وجود كلمة عفوية

التي من الممكن ان نتشارك فيها؛ هي اعادتني الى

عالم الخجولة المتشنج خالي الهواء

..... أو اليه, في كلماته- عالم

مكشوف, ضيق كما هو قفص المصعد,

غرباء يضغطون باصرار

و البعض منهم يرتدون لباس موحد

... أو الى أي احد غير قانوني, بدون أوراق ثبوتيه,

الهواء يتعرق ضده,

كل نفس هو خطر. لا تجتمع

كلمة مع كلمة, أو عين مع عين.

7

بالطبع تتدفق الاشياء.

كنت تريد كوكب آخر؟

و في الحال, نحن نجلس هنا في سرعة

تفوق سرعة الصوت.

العجب انه اننا نستطيع ان نتكلم

انا اعني, تقريبا ,نتناقش.

Bulgarian

Spoor by Philip Gross (stanzas 4-7)

Translated into Bulgarian by Krasimira Ivleva

Следа

4.

Седнал с гръб към пътя готов съм да се хвърля

в пътуването, незнаещ нищо

освен че тук е тази сянка, различна от моята,

която хвърля, не, която хвърлят светлините зад

мен, на парчета, диаспора,

премествания, които обаче идват към мен,

стават по-ясни, ако тръгна към тях,

приближават се към убежната точка

там, където те, не, където ние ще, бъдем едно.

5.

Както в тоалетната на гарата

отражението ми в сивата полирана стомана,

прозрачното вглеждане в себе си

вървейки към автоматичната врата,

преди глухия звук от юмрук в корема

и хриптенето от отварянето...или

както силуета на баща ми

през размазания водопад

на умореното му говорене; кой

беше мъжът, когото видях вчера

в тактично заключеното болнично отделение

да се тътри към мен, с обръсната,

като против въшки, глава?

6.

Сега съм без езиците си (английски,

френски) и в претъпкания

InterCity влак за Den Haag

пространството около мен промени контурите си

между мен и другия до мен и

другия, поради липсата на каквато и да е обикновена дума която да си разменим; напомня ми

за едно тясно, душно, срамежливо пространство

... или за него, в своя свят от

голи думи, тесен като асансьорна кабина,

където непознати се блъскат,

някои от тях в униформа

... или за всеки нелегален, без документи,

въздухът потящ се срещу него,

всяко вдишване е риск. Не посрещай

думата с дума, окото с око.

7.

Разбира се, че нещата изтичат

Различна планета ли искаш?

Точно сега седим тук по-бързо

от скоростта на звука

Чудя се дали въобще можем да разговаряме

искам д кажа, да общуваме.

Catalan

Spoor by Philip Gross (stanzas 4-7)

Translated into Catalan by Montserrat Lunati

4.

Encarat cap enrere, estic a punt de caure

al meu destí sense avís previ

excepte per una ombra, semblant a la meva,

fragmentada per la, no, per moltes llums

darrere meu, una diàspora,

desplacements, que tanmateix continuen venint de cara

i són més clars si jo m'hi atanso,

si me'ls acosto fins al punt d'esvanir-se,

el punt on seran, no, serem, una sola cosa.

5.

Com en el bany de l'estació,

el meu reflex en l'acer gris, lluent,

el jo transparent que es veu

travessant la porta automàtica

abans del soroll que fa en obrir-se,

com un cop sord a l'estómac i un xiuxiueig... o

com la figura del meu pare

a través del vapor de la cascada d'aigua,

de les seves llengües destrossades; qui

era l'home que vaig veure ahir,

que se'm va atansar arrossegant els peus, el cap

afaitat com per desinfectar-lo,

a la sala d'hospital tancada amb pany i clau (amb molt de tacte)?

6.

Ara, sense les meves llengües (anglès

francès) i a l'InterCity

ple a vessar, passant per L'Haia,

canviada la forma de l'espai que m'envolta,

entre l'home assegut al meu costat i jo, i

l'altre, per la manca d'un mot informal

que podríem intercanviar; em fa pensar

en el món asfixiant i encongit del tímids

… o en ell, en el seu món despullat de paraules,

estret com la gàbia d'un ascensor,

amb estranys que se li acosten massa,

alguns amb uniforme

… o en qualsevol immigrant il·legal, sense papers,

l'aire que sua en contra seu,

cada alenada un perill. No mirar

als ulls, no respondre als mots.

7.

És clar que les coses es precipiten.

Vols un planeta diferent?

Ara mateix, seiem aquí més ràpids

que la velocitat del so.

La sorpresa és que siguem capaços d'enraonar,

vull dir, és clar, de conversar.

Dutch

Spoor by Philip Gross (stanzas 4-7)

Translated into Dutch by Tsead Bruinja

4.

Achteruit reizend, bereid ben ik

om ongewaarschuwd in mijn bestemming te vallen

maar er is die schaduw, niet veel anders dan mijn eigen

door zijn, nee, door een veelvoud aan lichten

achter me, in stukken gesmeten, een diaspora

van verschuivingen, die hoe dan ook door komen, aan

en helderder als ik op hen af stap,

ze dichter naar het verdwijnpunt trek

waar zij, nee, wij, één zullen zijn.

5.

Net als op het station in het toilet,

mijn spiegelbeeld in grijs gepolijst staal,

mijn zichtbare en doorzichtige zelf

naderend in de automatische schuifdeur

voorafgaand aan de maagstomp plof

en het puffen bij het opengaan… of

als de gedaante van mijn vader

door vallend water de waas

van zijn versplinterde talen; wie

was de man die ik gisteren zag

op me af sloffend, hoofd

geschoren alsof het ontluisd moest,

op de (tactvol) gesloten afdeling?

6.

Nu ik buiten mijn talen ben (Engels,

Frans) en in de drukke

Intercity door Den Haag,

de aard van de ruimte om me heen veranderd,

tussen mij en de volgende man, en

de volgende, door het ontbreken van een simpel woord

dat we delen konden; het brengt me terug

naar de verkrampte bedompte wereld van de verlegen

…of naar hem, in zijn van woorden naakte

wereld, zo krap als een liftcabine,

vreemden te dicht tegen je aan gedrukt

en enkelen onder hen in uniform

… of naar een illegaal, zonder papieren,

de lucht tegen hem aan zwetend,

elke adem een risico. Beantwoord geen

woord met woord, of oog met oog.

7.

Uiteraard stromen dingen.

Wil je een andere planeet?

Nu op dit moment, zitten we hier sneller

dan de snelheid van het geluid.

Het is een wonder dat we spreken,

ik bedoel überhaupt kunnen converseren.

Fresian

Spoor by Philip Gross (stanzas 4-7)

Translated into Frisian by Tsead Bruinja

4.

Achterút reizgjend, ree bin ik

om ûnwarskôge yn myn bestimming te fallen

mar der is dat skaad, net hiel oars as myn eigen

troch syn, nee, troch in mannichte oan ljochten

achter my, yn stikken smiten, in diaspora

fan ferskowingen, dy’t hoe dan ek troch komme, oan

en helderder at ik op se ôf stap,

se tichter nei it ferdwynpunt lûk

wêr’t sy, nee, wy, ien wêze sille.

5.

Lykas op it stasjon yn it toilet,

myn spegelbyld yn griis polyste stiel,

myn sichtbere en trochsichtige sels

yn de automatyske skodoar oankommend

foarôfgeand oan de magestomp plof

en it blazen by it iepengean... of

as it stal fan ús heit

troch fallend wetter de waas

fan syn fersplintere talen; wa

wie de man dy’t ik juster seach

myn kant op toffeljend, holle

skeard lykas moast it ûntluze,

op de (mei takt) sletten ôfdieling?

6.

No’t ik bûten myn talen bin (Ingelsk,

Frânsk) en yn de drokke

InterCity troch Den Haach,

de aard fan de romte om my hinne feroare,

tusken my en de folgjende man, en

de folgjende, troch it ûntbrekken fan ien simpel wurd

dat we diele koenen; it bringt my werom

nei de krampeftige bedompte wrâld fan de ferlegen

...of nei him, yn syn fan wurden neakene

wrâld, sa krap as in liftkabine,

frjemden te ticht tsjin dy oan drukt

en guon fan harren yn unifoarm

... of nei in yllegaal, sûnder papieren,

de lucht tsjin him oan swittend,

elk sike in risiko. Beäntwurdzje gjin

wurd mei wurd, of each mei each.

7.

Uteraard streame dingen.

Wolst in oare planeet?

No op dit stuit, sitte we hjir flugger

dan de faasje fan lûd.

It is in merakel dat we prate,

ik bedoel überhaupt konversearje kinne.

French

Spoor by Philip Gross (stanzas 4-7)

Translated into French by Gabrielle Pillet

EMPREINTES

4.

Tourné vers l'arrière, je suis prêt à tomber

dans ma destination sans avertissement

sauf qu’il y a cette ombre qui ressemble à la mienne

projetée par sa, non, par de multiples lumières

derrière moi, en fragments, en diaspora,

en déplacement, qui viennent quand même et reviennent

et deviennent plus claires si je m'avance vers elles

si je les attire à moi jusqu'à l'évanouissement,

où elles seront, non, nous ne serons qu'un.

5.

Comme dans les toilettes de la gare,

dans l'acier gris poli, mon reflet

le moi en totale transparence

qui avance dans la porte automatique

avant le bruit sourd tel un coup dans le ventre

et le soupir de l'ouverture … ou

comme la silhouette de mon père

à travers le tourbillon de l'eau qui court,

celui de ses langues éclatées; qui

est cet homme que j'ai vu hier

s'approcher de moi en se traînant, tête

rasée comme pour l'épouiller,

dans la salle (soigneusement) verrouillée?

6.

Je suis maintenant au-delà de mes langues (Anglais,

Français) et installé dans un train

InterCity bondé qui traverse Den Haag,

la forme de l'espace autour de moi s'est altérée,

entre moi, et l'homme d’à côté, et

celui d'à côté, par l’absence d'une parole familiėre

que nous aurions pu échanger; cela me rappelle

le monde étouffant et étriqué des timides

… ou bien lui, dans son monde

sans mot, étroit comme un ascenseur

où des inconnus se serrent trop proches

certains portent un uniforme

… ou bien le clandestin, sans papiers,

l'air transpire autour de lui,

chaque souffle est un danger. Ne rends pas

mot pour mot, oeil pour oeil.

7.

Naturellement les choses se versent.

Vous voulez une planète différente?

En cet instant, nous voilà assis,

plus rapides que la vitesse du son.

C'est merveilleux que l'on se parle,

que l'on converse même.

Frisian

Spoor by Philip Gross (stanzas 4-7)

Translated into Frisian by Tsead Bruinja

4.

Achterút reizgjend, ree bin ik

om ûnwarskôge yn myn bestimming te fallen

mar der is dat skaad, net hiel oars as myn eigen

troch syn, nee, troch in mannichte oan ljochten

achter my, yn stikken smiten, in diaspora

fan ferskowingen, dy’t hoe dan ek troch komme, oan

en helderder at ik op se ôf stap,

se tichter nei it ferdwynpunt lûk

wêr’t sy, nee, wy, ien wêze sille.

5.

Lykas op it stasjon yn it toilet,

myn spegelbyld yn griis polyste stiel,

myn sichtbere en trochsichtige sels

yn de automatyske skodoar oankommend

foarôfgeand oan de magestomp plof

en it blazen by it iepengean... o

as it stal fan ús heit

troch fallend wetter de waas

fan syn fersplintere talen; wa

wie de man dy’t ik juster seach

myn kant op toffeljend, holle

skeard lykas moast it ûntluze,

op de (mei takt) sletten ôfdieling?

6.

No’t ik bûten myn talen bin (Ingelsk,

Frânsk) en yn de drokke

InterCity troch Den Haach,

de aard fan de romte om my hinne feroare,

tusken my en de folgjende man, en

de folgjende, troch it ûntbrekken fan ien simpel wurd

dat we diele koenen; it bringt my werom

nei de krampeftige bedompte wrâld fan de ferlegen

...of nei him, yn syn fan wurden neakene

wrâld, sa krap as in liftkabine,

frjemden te ticht tsjin dy oan drukt

en guon fan harren yn unifoarm

... of nei in yllegaal, sûnder papieren,

de lucht tsjin him oan swittend,

elk sike in risiko. Beäntwurdzje gjin

wurd mei wurd, of each mei each.

7.

Uteraard streame dingen.

Wolst in oare planeet

No op dit stuit, sitte we hjir flugger

dan de faasje fan lûd.

It is in merakel dat we prate,

ik bedoel überhaupt konversearje kinne.

German

Spoor by Philip Gross (stanzas 4-7)

Translated into German by

Béatrice Gonzalés-VAngell and Marc J. Schweißinger

4.

In entgegengesetzter Fahrtrichtung fahrend bin ich bereit,

Ungewarnt mein Reiseziel zu erreichen.

Abgesehen von diesem Schatten, der meinem sehr ähnlich ist,

Zerfallend durch seine, nein durch viele Lichtquellen,

Hinter mir in Bruckstücke, eine Diaspora,

Ortswechsel, die so oder so vor sich gehen,

und deutlicher werden, wenn ich mich in ihre Richtung bewege,

Sie näher bringe an den Punkt des Verschwindens

Wo sie eins, nein, wo wir eins werden.

5.

Während ich in dem Bahnhofswaschraum

Meine Wiederspiegelunge in dem grauen polierten Stahl sehe.

Das Visvai des Selbst vorwärts gehend

Zur automatischen Tür fortschreitend

Kurz bevor der dumpfe Schlag in den Magen aufprallt

Und dem Keuchen der Türöffnung... oder

Wie die Gestalt meines Vaters

Hinter dem trüben Wasservorhang

Seiner zerschlagenen Sprache; wer

Ist der Mann, den ich gestern sah?-

Schleppend zu mir kommend

Kahlrasiert, als ob er entlaust wird,

in dem (taktvoll) abgeriegelten Hinterhof?

6.

Nun bin ich außerhalb meiner Sprachsphäre (Englisch,

Französisch) in dem überfüllten

Intercity durch Den Haag.

Die Form des Raumes um mich her ändert sich

Zwischen mir und dem nächsten Mann, und

Dem nächsten durch den Mangel eines gewöhnlichen Wortes,

Das wir austauschen könnten, es erinnert mich

An die verkrampfte luftleere Welt der Scheuen.

Oder an ihn in seiner wortlosen

Welt, so eng wie ein Aufzugsschacht,

Fremde zu eng zusammengedrängt

Und einige von ihnen in Uniform

Oder an jedweden Illegalen ohne Papiere,

In der um ihn erhitzten Luft,

Jeder Hauch ein Atemzug. Wage nichts,

Auge um Auge, Wort um Wort.

7.

Natürlich strömen die Dinge.

Willst Du einen anderen Planeten?

Gerade jetzt sitzen wir hier, uns

Schneller fortbewegend als die Geschwindigkeit des Schalls.

Das Wunder ist, dass wir sprechen können,

Ich meine uns überhaupt unterhalten.

Greek

Spoor by Philip Gross (stanzas 4-7)

Translated into Greek by Georgios Tziakos

4.

Κοιτώντας προς τα πίσω, έτοιμος να χυθώ

Μες στον προορισμό μου, χωρίς να το σκεφτώ

Τη σκιά μου βλέπω, ή αλλουνού κανένα;

Που ένα φως τη ρίχνει – όχι, πολλά τη ρίχνουν,

Πίσω μου, θρύψαλα, διασπορά

εκτοπίσεις, που πλησιάζουν προς εμένα,

καθαρίζουν σαν πάω κοντά τους,

να τις μαζέψω εκεί όπου χαθούν

όπου αυτές – όχι, εμείς θα γίνουμε ένα

5.

Όπως στην τουαλέτα του σταθμού,

η αντανάκλασή μου στο γυαλισμένο ατσάλι

ο διαφανής κι αφανής εαυτός μου

προς την αυτόματη πόρτα προχωρεί

πριν τον γδούπο, στο στομάχι σαν γροθιά

και το σύριγμα σαν ανοίγει… ή

σαν του πατέρα μου να φαίνεται η μορφή

μες απ’ του τρεχούμενου νερού την όψη τη θολή

σαν τις θρυμματισμένες γλώσσες του; Ποιος

ήταν ο άνδρας που είδα χθες

να πλησιάζει, τα πόδια σέρνοντας, με κεφάλι

ξυρισμένο λες και βγήκε από ξεψείρισμα

στην (διακριτικά) κλειδωμένη κλινική;

6.

Τώρα είμαι έξω απ’ τις γλώσσες μου (Αγγλικά,

Γαλλικά) και μπαίνω στο γεμάτο

ΙντερΣίτυ μέσω Χάγης

το σχήμα του χώρου γύρω μου έχει αλλάξει

ανάμεσα σε μένα και τον διπλανό, και τον

παραδίπλα, με την απουσία μιας λέξης

που ίσως ανταλλάζαμε˙ Με επαναφέρει

στον ασφυκτικό των ντροπαλών τον κόσμο

… ή σε κείνον, στον απογυμνωμένο από λέξεις

κόσμο, στενό κλουβί ανελκυστήρα

άγνωστοι στριμώχνονται πολύ κοντά

κάποιοι απ’ αυτούς φορούν στολή

… ή σε κάποιον λαθραίο, χωρίς χαρτιά,

ο αέρας γύρω του ιδρώνει,

κάθε ανάσα ένα ρίσκο. Να μη συναντηθούν

ούτε λέξεις, ούτε μάτια.

7.

Μα φυσικά τα πάντα ρέουν

Τι θες, άλλο πλανήτη;

Τώρα καθόμαστε δω, πιο γρήγορα

κι απ’ την ταχύτητα του ήχου.

Το θαύμα είναι που μπορούμε και μιλάμε,

που συζητάμε καν, θέλω να πω.

Hungarian

bed (part 1) of bed and grave by Tsead Bruinja

Translated in Hungarian by Russell Travenen Jones

dunyha és sír

a szavak, amiket

ételre, kanálra, s az asztali tálra használsz

mások, mint

amiket nekem tanítottak ételre, kanálra, s tálra

és amikor hozzám érsz, néha

teljesen máshol érintesz, mint

a szavak, amiket

ételre, kanálra, s az asztali tálra használsz

mások, mint

amiket nekem tanítottak ételre, kanálra, s tálra

és amikor hozzám érsz, néha

teljesen máshol érintesz, mint

ahol a nővérem

belém csípett, ha csúfoltam

vagy ahol anyukám kicsit

erősebben csutakolt

ugyanazzal a dunnával takarózunk

csak a te dunyhád

lágyabb mint az enyém, ami majdnem úgy hangzik

mint a nagy folyó

apádat és anyádat

nagyapáidat, nagyanyáidat

máshogy hívják

sosem bújtak oda hozzád

sosem csókoltak meg

vagy mosdattak le

ugyanabban a világban élünk

odabújok hozzád

megcsókollak

most már ugyanúgy hívjuk

a tárgyakat is

a dunnám és a csókjaim

minden évben

egyre lágyabbak

(cont. unused in performance)

tudom, mi lesz a holmimmal

és a pénzemmel

amikor meghalok

de azt sehol se

írtam le

hogy meztelenül, egy szál takaróba csavarva

szeretnék bekerülni a földbe

hogy hol, az teljesen mindegy

anyám a gyerekeitől messze kívánkozott

úgy gondolta

nekünk el kell mennünk

az apjának apja mellé

temették

nagyapám szinte naponta

kiment hozzá

nagyapám és nagyanyám szép rendesen együtt fekszenek

a templom mellett, amibe nem jártak

közel a házukhoz

ott ahol nagyapa almát hámozott neki

és egy bambusz horgászbottal váltott csatornát

amit sosem néztünk tovább egy másodpercnél

hármuk közül egy sem nyugszik abban a földben,

ami fölött született,

de sosem húsz mérföldnél távolabb

onnan, ahol lakom

nem látszik a sírjuk

s egynapi járóföldnél messzebb van

leeuwarden pedig

messzebb van amszterdamtól

mint fordítva

most jövök rá, hogy én is másutt vagyok

indoneziában zimbabwében

és nicaraguában kopott a bőröm, hullott a hajam

ott vizeltem, és az éttermeikben ebédeltem

a test mindig megújul

s egyetlen porcikája sem a régi

és mikor majd elenyészik, a lelkem is elmúlik vele

ezért az üres testet nincs értelme visszavinned

hol hagyod majd, nekem majdnem mindegy

de ugye tudod, azt szeretném,

meztelenül, pokrócba tekerve tegyétek a földbe

és ha netalántán

újra hívő leszel akkor

mielőtt a rögök

hátrahagyott csontjaimra hullanak

dobj utánuk kérlek

egy bambusz horgászbotot

Italian

grave (part 2) of bed and grave by Tsead Bruinja

Translated into Italian by

A. Fochi, V. Motta and M. Donovan

la tomba

So bene dove la mia roba

i miei soldi andranno

quando morirò

ma da nessuna parte

lasciato ho scritto

che nudo in terra entrare

voglio in un lenzuolo

dove non mi importa

mia madre si e’ allontanata dai figli

perchè staccarci dovevamo

così pensava lei

accanto al padre di suo padre

è stata seppellita

il nonno ci andava quasi

ogni giorno

nonno e nonna sereni giacciono

a fianco della chiesa in cui non credevano

accanto alla loro casa

dove il nonno le sbucciava la mela

e cambiava i canali con una canna da pesca di bambù

mai più di un secondo abbiamo visto un canale

nessuno dei tre giace nella terra

sopra a cui era nato, ma neppure

più lontano di venti miglia

da dove vivo io

le loro tombe non le vedi

né ci vuole un giorno di cammino per raggiungerle

inoltre leeuwarden

è più lontano da Amsterdam

che in senso inverso

e solo adesso comprendo che sono già altrove

ho lasciato pelle, capelli in indonesia zimbabwe

e nicaragua

ho urinato e mangiato nei loro ristoranti

il corpo si rinnova

niente di te alla fine è uguale

e quando morirà sarà la fine anche dell’ anima mia

perchè allora restituire un cadavere vuoto?

dove lo lasceremo non m’interessa

ma tu sai che voglio entrare in terra

nudo in un lenzuolo

e caso mai tu avessi allora

di nuovo la fede ritrovata

getta prima che le zolle cadano

sulle ossa da me lasciate

una canna da pesca di bambù

assieme a loro

Luxemburgish

bed (part 1) from bed and grave by Tsead Bruinja

Translation by Sarah Hanech in to Luxembourgish

bed

D'Nimm di du benotz

fir d'Bestéck, den Teller an d'Tass um Dësch

sën net di Nimm

déi ech fir d'Bestéck an de Service geléiert han, an

wanns du mich beréiers, hainsto beiéiers du

ee komplett anneren Deel va mer

wéi wa méng Schwëster

mich gepëtzt hatt wa mer gerolzt han

oder wa méng Mamm

mich gudd geschrubbt hatt

Mer schlofen an deem selwischte Bett

mee däint as mi kuerz

a mäint kléngt ischter

wi d'Meckeren van enger Geess

däi Papp an déng Mamm

däi Bopa an déng Boma

si heeschen annischt

Su han ni mat der gekuschelt

der ee Kuss gien

oder han dich an der Bidden geschrubbt

Mer liewen an der selwischter Welt

Ech kuschelen mat der

gien der ee Kuss

Fir déi Saaschen benotzen mer lo

di selwischt Nimm

däi Bett an deng Kussen

gi mi aal

va Joër zu Joër.

Persian

Bed and Grave by Tsead Bruinja

Translated into Persian by: Seyed Hossein Heydarian

به نام خدا

Bed & Grave

من و تو با دو زبان

نامهایی که تو می نهی

برای یکایک وسائل روزمرۀ مان

نامهایی دیگرند

و

برای احساساتمان

برای لمسهایمان

برای

شوخیهای کوچکمان

خاطراتمان

من و تو، هر یک، چیزی می گوییم

گاهی من طولانی تر می گویم: گاهی تو

گاهی من کوتاه تر می خوانم: گاهی تو

و شبها

من در تخت کوتاه تری می خوابم

همیشه مادرت را جور دیگری صدا می کنی

و آن یکی را که دوستش داشته ای

ما

هر دو در یک دنیا زندگی می کنیم

و من

برای آنچه که برایمان نام واحدی دارد

تو را در آغوش می گیرم

و

بوسه می زنم

تخت تو و بوسه های تو

طولانی تر می شوند

در سالگرد هم زبانی مان

Spoor by Philip Gross stanzas 4 - 6

4.

به عقب می نگرم

آمدم که بیفتم

به سوی مقصدی که از پیش نمی دانستم

اما شبحی در اینجاست، که به من مانند نیست

افتاده با نورهایی فراوان

از پس من، تکه تکه شده: مثل در به در شدن یک تبار

5.

در دستشویی ایستگاه بین راه ایستاده ام

تصویر خاکستری من در فلز جلاخورده روبه رویم افتاده است

آنجا خود را و بعد خود را در درهایی که خودکار باز و بسته می شوند

می بینم

…

یب که یاد تصویر پدرم می افتم

یاد زبان از هم گسیختۀ او؛

انگار همین دیروز بود که به سوی من به سختی قدم می نهاد

صورتش را از ته ته تراشیده بود

از آن سوی اتاق بخش، که به ظرافتی قفل شده بود

6

اکنون من زبانی ندارم و در داخل قطار اینترسیتی به سمت دن هاگ می روم

اینجا فضا صورت دیگری دارد

بین من و مرد بعدی،

و آن یکی، بدون گفتن کلامی خودمانی

به یاد می آورم که ما باید چیزی را تقسیم کنیم

در این دنیای تنگ و کوچک و دم کرده

یا برای او با دنیای واژه های

بی پرده اش

مردم اینجا، مثل درون اتاقک آسانسور،

به هم زور می آورند

آنها که گاه لباس رسمی شان را بر تن کرده اند

واژه رو بروی واژه: چشم روبروی چشم

Polish

bed and grave byTsead Bruinja

Translation from English into Polish by

Agata Kalisz

łóżko i grób

słowa których używasz

dla noża i szklanki na stole

nie są pierwszymi słowami

które poznałem dla noża i szklanki

a kiedy mnie dotykasz dotykasz czasami

zupełnie innej części mnie

niż kiedy moja siostra

szypie mnie gdy ją zezłoszczę

lub kiedy matka z większą czułością

mnie myje

śpimy w tym samym łóżku

ale twoje jest krótsze

a moje brzmi bardziej

jak szczekanie psa

twój ojciec i matka

twoi dziadkowie i babki

nazywają się inaczej

oni nigdy nie przytulają się do ciebie

nie całują

i nie czyszczą twarzy

my żyjemy w tym samym świecie

przytulam się do ciebie

i całuję

dla różnych rzeczy używamy

już tych samych słów

twoje łóżko i pocałunki

stają się dłuższe

co roku

wiem co się stanie

z moimi rzeczami i majątkiem

kiedy umrę

ale nigdzie

nie zapisałem

że chcę wstąpić w ziemię

nagi w pledzie

nie ma znaczenia gdzie

moja matka chciała być daleko od dzieci

bo musieliśmy się rozwijać

według niej

pochowano ją koło ojca jej ojca

dziadek chodził tam prawie

codziennie

mój dziadek i babka leżą ładnie razem

przy kościele w który nigdy nie wierzyli

obok ich domu

w którym dziadek obierałby dla niej jabłko

i zmieniał programy bambusowym patykiem

nigdy nie patrzeliśmy na program dłużej niż sekundę

i wszyscy troje nie leżą w ziemi

na której wierzchu się urodzili ale nigdy dalej

niż 20 mil

stąd gdzie mieszkam

nie możesz zobaczyć ich grobów

ani znaleźć rzadnego idąc cały dzień

fryzja poza tym

jest bardziej oddalona od amsterdamu

niż odwrotnie

i właśnie zrozumiałem że jestem już gdzie indziej

zostawiłem skórę i włosy w indonezji zimbabwe

i nikaragui

sikałem i jadłem w ich restauracjach

ciało odnawia się samo

żadna twoja część nie jest taka sama u kresu

i kiedy ono umrze bedzie to koniec mojej duszy

więc powrót do pustych zwłok byłby bezcelowy

dokąd odejdziesz nie ma dla mnie znaczenia

ale wiesz że chcę wstąpić w ziemię

w pledzie nagi

i na wypadek gdybyś przypadkowo

zaczęła być wtedy znowu wierząca

rzuć zanim ziemia

spadnie na szczątki które po sobie zostawię

bambusowy patyk

razem z nią

Spanish

bed and grave by Tsead Bruinja

Translated into Spanish by Montserrat Lunati

se dónde terminarán

mi dinero y mis cosas

cuando muera

pero en ninguna parte

he escrito

que quiero entrar en la tierra

envuelto en una manta, desnudo

me da igual dónde

mi madre quería estar lejos de sus hijos

porque teníamos que volar

creía ella

la enterraron

junto al padre de su padre

mi abuelo iba allí casi

todos los días

mi abuelo y mi abuela yacen juntos

al lado de la iglesia en la que no creían

cerca de su casa

allí mi abuelo le pelaba una manzana

y cambiaba de canal con una caña de pescar de bambú

nunca veíamos el mismo canal durante más de un segundo

ninguno de los tres yace en la tierra

que le vio nacer pero ninguno reposa mas allá

de una distancia de 20 millas

desde donde yo vivo

no se pueden ver sus tumbas

o encontrarse con una tras un día de camino

además leeuwarden está

mucho más lejos de amsterdam

que no al revés

y me acabo de dar cuenta de que estoy en otro lugar

he dejado piel y cabellos en indonesia zimbaue

y nicaragua

he orinado y comido en sus restaurantes

el cuerpo se renueva

ninguna de sus partes es ya la misma

y cuando se muera será el final también de mi alma

por tanto devolver el cuerpo vacío sería inútil

dónde lo dejes me da igual

pero sabes que quiero entrar en la tierra

envuelto en una manta, desnudo

y en caso de que por casualidad

seas creyente de nuevo cuando me llegue la hora

antes de que la tierra

cubra los huesos que dejaré atrás

haz que reposen

junto a una caña de pescar de bambú

Welsh

bed and grave by Tsead BruinjaTranslated in Welsh by Jessica Mills

gwely & bedd

yr enwau a ddefnyddi di

am fwyd cwtleri a llestri

nid y rhain yw’r enwau cyntaf

a ddysgais i am fwyd cwtleri a llestri

a phan gyffyrddi di â fi mae’n weithiau

rhan hollol wahanol ohonof

i le byddai fy chwaer

yn pinsio fi ar ôl imi’i herio

neu le byddai mam yn ymdrechu bach fwy

wrth iddi f’olchi

cysgwn yn yr un gwely

dy un di’n fyrrach

a f’un innau’n debyg

i frefu’r da

dy dad a dy fam

dy dadcu a dy famgu

enwau gwahanol sydd ganddynt

gwtsion nhw di fyth

ni rhoion nhw sws i ti

defnyddiwn ni am y rheiny

yr un enwau nawr

dy wely a dy sws

tyfan nhw’n hirach

bob blwyddyn

lle bydd fy mhethau

a’m arian yn mynd

pan byddai’n marw

yr hyn dwi’n gwybod

ond nunlle

yr ysgrifennir

fy mod am cael fy nghladdu

yn noeth mewn blanced

lle ‘sgen i ddim ots

dyhead fy mam oedd pellter oddi wrth ei phlant

achos rhaid oedd symud ‘mlaen

yn ôl hithe

cafodd ei chladdu

ar bwys dad ei thad

aeth dadcu yno bron â bod

bob dydddadcu a mamgu sy’n gorwedd yn dwt gyda’i gilydd

ar bwys yr eglwys ni chreden nhw ynddi

wrth ochr eu cartref

lle byddai dadcu yn pilio afal i mamgu

a newid y sianel gyda gwialen fambŵ

wylien ni byth yr un sianel am hirach nag eiliad

gorweddan nhw tri

nid yn y ddaear bu’n wyneb i’w geni, ond nid yn fwy

nag 20 milltir ohoni

le dwi’n byw

ni weler eu beddau

ni ddarganfyddir run ohonynt dydd daith ar droed

leeuwarden ymhellach

sydd bellach i ffwrdd o amsterdam

nag o chwith

a dwi newydd sylweddoli fy mod man arall yn barod

gollyngais croen a blew yn indonesia simbabwe

a nicaragua

pisiais a bwytais yn eu bwytai

adnewydda’r corff

does run rhan yr un peth yn y diwedd

a phan byddai’n marw byddai’n ddiwedd hefyd i’m enaid

felly dychwelyd y celain ofer fyddai

lle’i gedwir sdim ots gen i

ond ti sy’n gwybod fy mod am iddo gael ei chladdu

mewn blanced yn noeth

ac os yr ydych ar hap

yn dod yn grediniwr eto pryd ‘ny

tafla cyn y tyweirch

gad ddisgyn ar yr esgyrn

y gadewais ar eu hôl

gwialen fambŵ

Italian Translation

The dialect of the scrub in the dry season

withers the flow of English. Things burn for days

without translation, with the heat

of the scorched pastures and their skeletal cows.

The issues that we found in translating this passage were very similar to those found by the French group. It was not possible to find such short translations for a number of the monosyllabic words used in the source text, resulting in some of the lines being somewhat longer in the Italian version.

A second issue was the line “flow of English”, which seemed to crop up as a challenge for every group. We decided that if we used ‘English’ in a non-English poem the word would become totally irrelevant (possibly the reader would have no idea how English flows). To overcome this, we used a more general concept of language itself, as the flow of words/language is something that everyone can relate to. Tied in with this, we found that the Italian word “fiume” (river) rather than “flusso” (flow) is used when talking of language or words.

We also found the same problem in the word 'scorched' that the French group found. The word translates in Italian as 'bruciare' (to burn) which we had already used previously in the passage. To avoid repetition, as has been done in the source text, we decided to use the word 'indarire', which means sun-dried in the sense of grass. We felt that this was a more applicable word since the text was speaking of a pasture.

The final problem that we noted was that of “for days”. In Italian the translation 'per giorni' would not have the same meaning of 'a long period' and so we added the word 'tanti' (many). This did lengthen the line of the poem, but not significantly enough to change the structure a great deal. As none of us in the group were first-language Italian, however, it is quite difficult to be sure that what we have written is the most accurate/appropriate translation.

James Hammacott, Chris Smiddy,

Claudia Hutchinson

Il dialetto della sterpiglia nella stagione secca

appasse il fiume del linguaggio. Le cose bruciano per tanti giorni

senza traduzione, con il calore

delle pasture indaridite e le loro mucche scheletrice.

Spanish Translation

The dialect of the scrub in the dry season

withers the flow of English. Thing burn for days

without translation, with the heat

of the scorched pastures and their skeletal cows.

As with Italian, French and Romanian, a conscious effort has to be made at times not to make the Spanish sound too poetic, or over laden with rhymes and alliteration that does not exist in the original.

This occurred in particular with the final line of the poem, and although I searched through many words for ‘skeletal’ in Spanish, I could not avoid the rhymes made between ‘pastos abrasados’ and ‘vacas lacias’ as the adjective must agree with the noun in gender, therefore giving the same sounds to the word endings. In the end, I had to leave it as there were other occasions in this section of the poem where I had managed to avoid this problem by finding other synonyms.

Another problem was the word ‘quemar’ (to burn) as the word ‘burn’ and the word ‘scorched’ would both be translated as the same in Spanish so I chose to use a different word to avoid repetition.

The other concern was to make sure that it flowed in Spanish. Obviously, it was impossible to re-create the exact number of syllables per line, but I consciously chose certain words which were either shorter or longer in length in order to make the Spanish version flow as much as possible.

Finally, when I translated ‘the flow of English’ I literally said ‘the fluidity of English’. I was torn between the word ‘corriente’ which more or less translates as ‘current’ and ‘fluidez’ (fluidity). I liked the word current because when I read the English it gave me this idea of flowing like water, but I chose ‘fluidez’ because in Spanish that word is most often associated with language, and so it fitted better with the poem’s context- ‘the fluidity of English’.

I also liked the comment made by one of my classmates that it was not necessary to include the word ‘English’ at this stage. This left me free to use the word ‘lengua’ in Spanish which means both language and tongue. I thought this gave a powerful image of language literally withering in the mouth. Maybe I overcompensated on this occasion but I felt that sometimes it is necessary to bring out an idea/theme that runs through the poem (in this case the idea of the English language being overtaken by Creole) whenever possible as there may be an occasion later in the poem where the translator has to ignore this image in favour of something else. In other words, it is a case of prioritising and trying to keep the ideas of the poem intact even if they do not appear in exactly the same line as the original.

Amy McGregor

El dialecto de las brozas en la época seca

marchita la fluidez de la lengua. Cosas queman por días

sin traducción, con el calor

de los pastos abrasados y las vacas lacias

Chinese Translation

旱季里的方言如同灌木丛一般

枯竭了英语的洪流。 他们燃烧了许多日子

然而却没有任何新生事物出现,有的只是烧焦的牧地上那不断散发的热气

以及骨瘦如柴的牛群。

The points I find now are some differences with what we did in Nov. 22 workshop.

Fist of all, I translate “scrub” to “灌木丛”,which in chinese means a geographical landscape, but combined with dialect, it does not make sense. To make it known to chinese reader, “如同灌木丛一般”would be appropriate.

And the second issue comes the line“flow of English”, which is a common challenge for each group. What confuses me here is the“English”since it has two meanings, either the english this language or english-speaking countries”, but the fist line tells me that they should be correspondent, so it is talking of english this language.

The third issue goes to“days”,with no plural in chinese, the translation“日子” would not have the same meaning“a period of time” because it does not translate the“s”, so here“些许”would be added.

In addition, the sequence of sentence is an important issue concerned in translation.

Regarding the line“with the heat of the scorched pastures”, I put the“热气”(central meaning)at the end of the sentence because in chinese, the central meaning are most of the time put at the end and“the scorched pastures” serves as the role of modifying, which would be put before“heat”.

Retranslate this poem into english:

The dialect in the dry season strives as the scrub

Withers the flow of English.things burn for days without newly things,with the heat of the scorched pastures and its roots showing.

Dongdong XU, Lan Lan, Lumeng Yang,

Ruby Chung

The dialect of the scrub in the dry season

withers the flow of English. Things burn for days

without translation, with the heat

of the scorched pastures and their skeletal cows.

Romainian Translation

Dialectul tufişului în sezonul uscat

ofileşte fluxul englezei. Lucrurile ard zile-ntregi

făr-a fi-nţelese, cu arşiţa

păşunilor pălite şi a vacilor scheletice.

In the first line of the poem I tried to keep the musicality of the text offered by the sounds /s/, /ʃ/ and /z/. Thus, I used words like tufiş (scrub), sezon (season) and uscat (dry).

The second line of the poem offered me the possibility of creating an alliteration using the stressed syllable of the word ofileşte (withers) and the stressed syllable of the word fluxul (flow). On the other hand, the same line was also an issue because of the literal translation of the word flow that I had to use. From my point of view, the use of /ʃ/, /ɛks/ and especially the voiced /z/ in only one line makes it sound a little bit too harsh. Although the word englezei is the biggest issue in this line because of its voiced /z/, I decided to keep it, as I think that this is a key word for any reader to understand the cultural background of the text. However, the problem of the voiced /z/ in the first part of the line got solved in the second part of the line where the word days offered me the possibility of using zile, counterbalancing in this way the harsh strength of this sound. Although I was not able to use only monosyllabic words for this part of the line, as is the case in the original text, I tried to shorten the Romanian version by using an aphaeresis – instead of saying zile întregi I chose to cut out the î and link the two words together. Fortunatelly, Romanian is a language that allows its users to recur to such linguistic tricks.

In the third line I chose a risky solution; I decided to leave out the obvious option traducere, which would be a literal and perfect equivalent of the word translation in English and I used instead without being understood. The main reason for which I chose to do this is simply because the word traducere would have sounded rather odd and would have disturbed the entire flow of the poem, especially because of the sound / tʃe/. Thus, I opted again to link together four words this time and instead of saying fără a fi înţelese, I used făr-a fi-nţelese, in order to make the text flow. This choice allowed me to bring in another alliteration using the voiceless fricative /f/. The flow of the text was also preserved with the use of sounds like /ʦ/, /s/ and /ʃ/.

The English version of the scorched pastures in the fourth line offered me the possibility of another alliteration - păşunilor pălite. One semantic issue that I had to deal with here was the choice of the best equivalent for the word scorched. One of the most obvious options was pârlite and a milder option was pălite. I chose the latter one thanks to the fact that this way the alliteration is made up of an entire syllable and not only the first consonant.

All in all, from a semantic point of view, I have not encountered many issues, Romanian offering me a numerous variety of options worthy of taking into consideration. From my point of view, the most interesting part while working with this text was the phonetic puzzle that I had to ‚re-create’ in my translation. That is why my commentary is mostly based on phonetic issues. Fortunately, Romanian is a highly versatile language, both from a semantic and phonetic point of view (and maybe even a syntactic one) and it allows its users to use it creatively.

Mirona Moraru

The dialect of the scrub in the dry season

withers the flow of English. Things burn for days

without being understood, with the heat

of the scorched pastures and their skeletal cows.

French Translation

Le dialecte des broussailles pendant la saison sèche

Fane le flot de l’anglais. Les choses brulent des jours durant

Sans traduction, dans la chaleur

De prairies écorchés et de leurs vaches squelettiques.

The main issue that we had while translating this piece was the fact that the translation in French uses up more syllables and requires more definite articles, making the lines longer than in the original. One example of this was when we translated ‘things burn for days.’ We had to add the word ‘durant’ because simply saying ‘les choses brulent des jours’ does not make sense in French. However, adding ‘durant’ makes it translate to ‘for lasting days’ which somewhat increases the time lapse in the poem.

When translating ‘the flow of English’ the first word we thought of to translate ‘flow’ was ‘flux,’ but then we realised that this word referred to the sea and the tide more than a river, and so we changed it to ‘flot’ in order to capture the imagery and make it tie in better with the concept of speech.

Another challenge we had was with the word ‘scorched’ which commonly translates as ‘brulé’ in French, but we did not want to use this word since it would be repeating the same verb for the word ‘burn’ two lines above. Instead we chose the word ‘écorché’ which, although it usually translates as ‘skinned’ or ‘scraped’ in French, can also be used to describe burns on the skin.

Finally, we had an issue with the word ‘pastures’ as we could not decide whether to use ‘pâturage’ (the literal translation) or ‘prairie,’ which is less technical and which may provide more imagery. In the end we used the latter, as we realised that there would already be a lot of syllables in this line.

Rhiannon Batcup, Gwenllian, Jones Natalie Soper

The dialect of the undergrowth during the dry season

Withers the stream of English. Things burn for days

Without translation, in the heat

of the skinned meadow and their skeletal cows.

Hungarian Translation

Język buszu w czasie suszy miażdży płynność mowy. Sprawy palą się długimi dniami pozbawione wyjaśnienia, gorącem przypalonych pastwisk i krowich szkieletów. Każdy rzeczownik to pniak z korzeniami na wierzchu, kreol języka rozpościera się jak ziele aż cała wyspa będzie pokryta, pózniej deszcz zaczyna padać akapitami i zaciera stronę, zaciera szarość wysp, szarość oczu, sztorm jest dziką owłosioną pięknością.

We translated the word ‘dialect’ into ‘language’ as we felt it helps to put across the sense of the sentence. We have changed the word ‘English’ to ’Speech ‘because as we thought it made the text sound better in Polish. It also made the text a little smoother. The reader can figure out that it is English language on author’s mind. We have not translated the word ‘kreol’ as it has not got Polish equivalent.

The speech of the bush in the time of drought crushes the flow of speech. Things burn for long days without explanation by the heat of cows skeletons. Every noun is a stump with its roots out, kreol of the language spreads like weed until the whole island will be covered, then the rain begins to come in paragraphs and hazes the page, hazes the grey of islets, the grey of eyes, the storm is a wild hairy beauty.

German Translation

1. Das Verdorren des Gestrüpps in der Trockenzeit

2. stört fließendes Englisch. Tagelang brennend

3. ohne Übersetzung, die Hitze.

4. des versengten Grases und dessen knochigen Kühe.

Line 1:

We omitted 'dialect', due to the effect of saving as many syllables as possible. As Mr Göske stated, German words tend to be a lot longer, so a larger amount of syllables is unavoidable, but the aim is to reduce the number as much as possible to maintain the music as well as possible. We are aware of the link between the keywords relating to language (dialect, English, fluent, etc) and we tried to maintain them as much as we could, however, minor sacrifices had to be made.

Line 2:

'Withers' has been translated as 'interrupts' as the process of withering has already been emphasised in line 1 ('Verdorren') and to save syllables.

'The flow' has been transformed into 'flowing' which can also mean 'fluent' which refers to the key theme mentioned above.

'Things' has been omitted as we understood it as too broad or unclear which can as well be expressed as 'burning' instead of 'things burn'. This, again, decreases the number of syllables.

Line 3:

'With' has been omitted, too, as we agreed that the same effect can be achieved without using this preposition and as the same time reduces syllables in the German translation.

Line 4:

The genitive construction as in 'of the scorched pastures' does not exist in the German, we use a specific article the indicates the genitive case.

'skeletal' does not exist in German either, it would have to be 'skeleton-like' or 'like a skeleton' which, again, does not fit into the melodic pattern and has therefore been substituted by the translation of 'bony'.

The withering of the scrub in the dry season

interrupts the flowing/fluent English. Burning for days

without translation, the heat

of the scorched pastures and their bony cows.

Arabic Translation

The dialect of the scrub in the dry season

wither the flow of English. Things burn for days

without translation, with the heat

of the scorched pastures and their skeletal cows.

The local language in the dry season

shrinks the flow of English language.

Things burn for days without translation,

with the heat of burning pastures and their skeletal cows.

It was difficult to translate some terms from English to Arabic. It was also difficult to find the equivalent of some words. During the Arabic translation, we have to omit some words in order to maintain the structure and to make a meaning for the sentence. For example we had to omit the words “scrub”. Such word does not fit when we translate it to Arabic. And, when we translate it literally, it was difficult to find the proper meaning, as it has different meanings. In addition, when we tried to translate it as a free translation, it does not make any sense in Arabic. This is because of its location in the sentence.

To make it more sense, we had to translate the first sentence as “The local language in the dry season shrinks the flow of English language”.

Translating English poems to Arabic, the target language becomes irrelevant and nonsense by which the reader of the target language can not understand the word relevance. In Arabic language, we usually maintain the rhythm and tone. Therefore when we translated to Arabic, this poem turned to be a prose.

The second sentence, we translate it literally, which also does not make sense in Arabic, but it was easy to find the equivalent words in Arabic.

Ansaf Elmajdalawi, Sady Elseesi

اللغة المحلية في موسم الجفاف

تقلص انسيابية اللغة الانجليزية.

الأشياء تحترق لأيام بدون ترجمة،

مع حرارة المراعي المحروقة والأبقار الهزيلة

Polish Translation

Mowa buszu w czasie suszy miażdży

przepływ mowy. Rzeczy bez powodu

palą się długimi dniami gorącem

spalonych pastwisk i krowich szkieletów.

The speech of the bush in the time of drought

crushes the flow of speech. Things without reason

burn for long days by the heat

of burnt pastures and cows skeletons

Katarzyna Bialas-Swart, Rafal Jennek, Maciej Mechacki

The speech of the bush’: we translated the ‘speech’ literally as ‘speech’ (mowa), we were also thinking that ‘language’ might have been better (język), but that would not have agreed with the ‘speech’ used in the second line (the flow of the language would not work well).

‘crushes the flow’: we chose ‘miażdży’ for ‘[it] crushes’, which is a translation that gives an idea of crushing extremely hard; ‘the flow’ became ‘przepływ’, rather than ‘pływ’, although both mean virtually the same, the first adds an additional meaning of ‘through’ (the suffix ‘prze-‘). Nevertheless, we are not entirely sure how a flow of speech could be crushed as usually, only solid substances can be crushed, not liquids or gases (we treat speech, in the physical sense, as a series of waves of pressure which propagates through air, thus they cannot practically be crushed).

‘Things without reason’, here, we were very literal again – ‘things’ became simply ‘rzeczy’, while ‘reason’ was more problematic. We used ‘powód’, in the sense of a ‘cause’ (there is no reason why the things burn), however, we might have translated ‘reason’ as ‘rozum’, in the sense of being intellectually reasonable, being able to think logically, or as ‘rozsądek’ (as ‘sense’ in the expression ‘common sense’ – ‘zdrowy rozsądek’). Because Polish offers the three different names (and perhaps more), by choosing ‘powód’ (cause), we might have missed the play on words, i.e. ‘things have no reason (are incapable of thinking) and they ‘burn’ and, at the same time, ‘there is no reason why the things burn’, nevertheless, the poem provides a reason why they burn (because of the heat). Our third possible rendering would have been: ‘Rzeczy bez sensu palą się...’ i.e. ‘it is pointless/useless why the things burn’, it would introduce another hidden meaning if translated literally – ‘things without sense burn...’, which could be understood by a Polish person as the aforementioned ‘pointless/useless’, or ‘without meaning’, ‘meaningless’. The difference being that the second understanding would mean that the things have no inherent meaning in themselves, rather than it is useless that they burn. Hence, we decided to choose ‘powód’, for the benefit of simplicity, but it could be debated whether it was a good choice.

‘for long days by the heat’, ‘for long days’ was quite easy and literal – ‘długimi dniami’, whereas for ‘by the heat’, we could have rendered two, in our opinion, equally valid options – ‘gorącem’, ‘skwarem’ and two slightly worse options – ‘upałem’ or ‘ciepłem’ (‘upałem’ would not sound correct and ‘ciepłem’ would not convey the idea of ‘very hot’, because it could be translated as ‘warm’, or ‘hot’ and hence could have been too mild). We chose ‘gorącem’, because ‘skwarem’ would have produced an alliteration: ‘skwarem spalonych’, where it is not present in the original: ‘heat of burnt’, so we did not want to improve (?) the form, which might not be any improvement after all.

‘burnt pastures’ we translated literally as ‘spalonych pastwisk’, although, at first, we used ‘przypalonych’, but later we realised that it sounds like ‘slightly burnt’, which would not fit our reading of the gloomy atmosphere of the pastures, so we chose ‘spalonych’ – ‘completely burnt’.

Next, again, we translated literally ‘cows skeletons’, as ‘krowich szkieletów’ – conveying the gloomy and dark vision of burnt bones lying on the pastures, rather than e.g. cows, which are so emaciated that one could see their bone structure.

Finally, we were surprised that we could find so much meaning and so many possible interpretations, and hence translations, in such a short text.

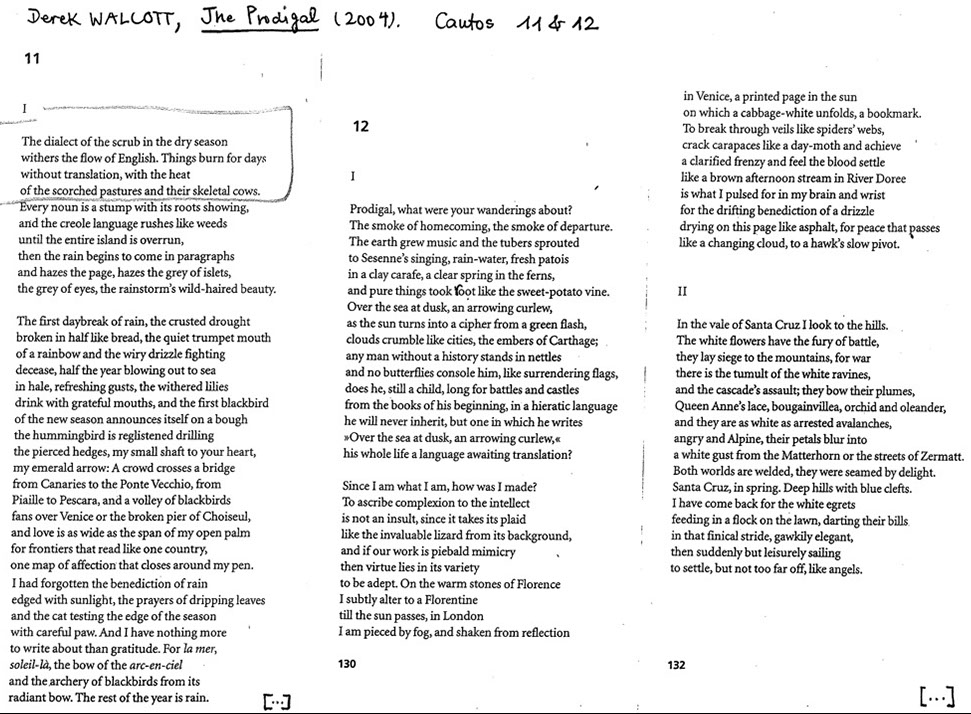

Daniel Göske

reads from his translation of

Derek Walcott's

The Prodigal

Stanzas 11 & 12

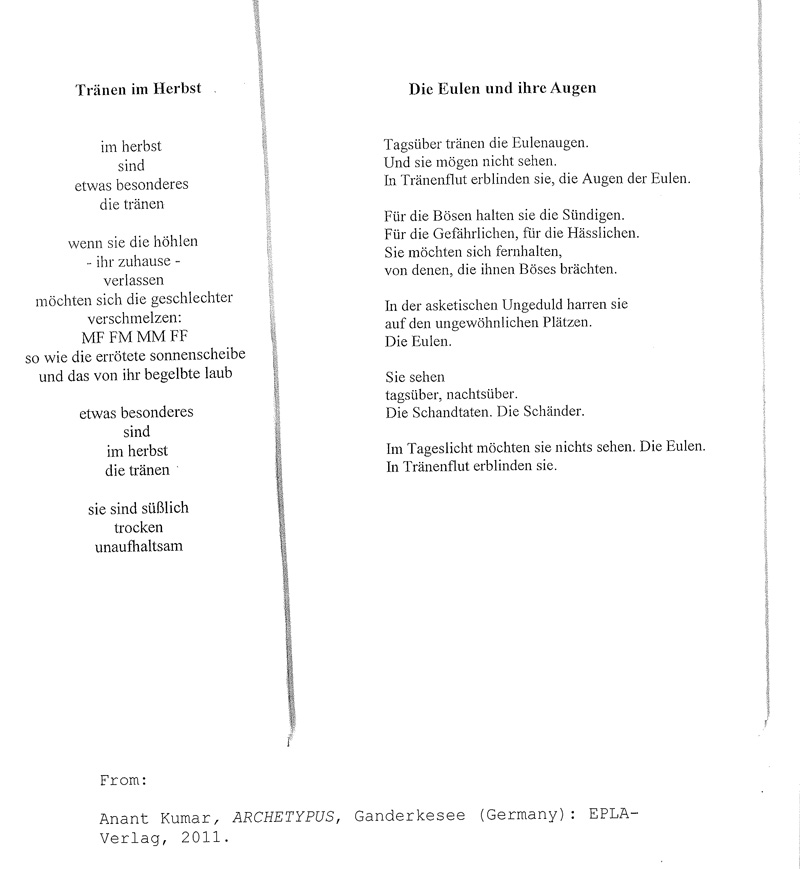

Anant Kumar

Poetry

Translation Workshop

"...It was thoroughly enriching to see my poetry/ poems through the lenses of translators live at work. Their queries opened me new windows to understand and enjoy my words. Enjoyable. Refreshing. Enriching..."

A.K.

Turkish

Die Eulen und ihre Augen

by

Seda Okuyucu

Baykuşların Gözleri

Gündüzleri baykuşların gözleri kapanır,

Bir şey görmek istemezler.

Güneş ışığında sanki kör olur baykuşlar.

Günahlar peşlerini bırakmaz,

Tehlikeler, kötülükler…

Baykuşlar onlara zarar veren

Tüm bu kötülüklerden uzak durmak isterler.

Büyük bir sabırsızlıkla beklerler

Kuytu köşelerinde

Akşamı, baykuşlar.

Gündüzleri görmezler baykuşlar,

Geceleri ise tüm kötülükleri görürler,

Gün ışığında bir şey görmek istemezler baykuşlar.

Gözleri dolar sanki kör olurlar.

The Eyes of Owls

The eyes of owls are closed during the day,

They don’t want to see anything.

They go blind by the sunlight.

Their sins never stop following them,

Dangers, evils…

They want to keep them away from

All these dangers and evils harmed them.

They wait for the evening

At their hidden places impatiently to come out, owls.

The owls don’t see anything in the daytime,

But they see all the evils during the night.

They don’t want to see anything at daytime, owls,

Their eyes filled with tears with the sunlight

And they go blind.

Commentary

In poetry translation, the most important thing is to reflect the meaning of the source text in a logical way that can make sense for the target audience. If the translators follow a direct translation method, the translated text might fail. Therefore, what it should be done is that to make some slight adaptations according to the target culture and shape the translation in the light of the culture.

In this poem, I changed some points just to be able to make it more sensible and understandable for the Turkish audience. In our culture, the owls are not considered as good. They are believed not to bring luck to the people who see them. It is not a good sign to see an owl and especially at nights it brings bad luck. According to my culture, the owls don’t see anything during the day so they hide in their places until the evening and they come out in the evening. Thus I paid attention to the details and translated the poem according to my culture.

In the first verse, it says “during the day the owl eyes water” and I translated the line as “they eyes of owls are closed during the day” because if I translated it as it is in the original, it wouldn’t make sense for the target audience. In the same verse, for the phrase “in the flood of tears”, I preferred to translate it as “they go blind by the sunlight” as it is more sensible to reflect the meaning as a whole.

For the second verse, I made some changes to smooth the meaning. I wanted to change it not to create a bad impression about the poem because the owls in my country are already considered bad luck animals. Therefore, I used less strong words.

In the third verse, I translated the “ascetic impatience” just as “impatiently” as I could not explain it as it is in the source text. For the word “unusual places”, I chose “hidden places” because the owls wait in hidden places at daytime and you cannot see them and they come out in the evening. Therefore, I found appropriate to use such a word to reflect the meaning.

For the fourth verse, as they don’t see at daytime, I changed the sentence completely and said “they don’t see anything at daytime but they see all the evils at night”. I didn’t want to use the words in the original text.

For the fifth verse, I translated it as “their eyes filled with tears by the sunlight and they go blind”. I explained the reason why they go blind during the daytime. Therefore I render the meaning in “in the flood of tears” as “their eyes filled with tears”.

After all, the poetry translation is quite challenging to give the same message with different words. Also, culture is always a big factor playing a key role in the poetry translation. The translators should always regard to the cultural differences between two different languages and indicate their translation methods to transfer the message intended to be given in the source language into the target language.

Japaneese

Tränen im Herbst

Translation into Japanese

秋にの涙

秋に

涙は

特別な

ことだ。

洞窟を出ったら

〜お宅〜

性的は

交ざりたい

男女・女男・男男・女女

頬染めた天照大御神

と御神様が黄色になられた葉

のみたい。

特別な

ことだ

秋に

涙は

すこし甘いし、

乾燥し、

止められない。

Aki ni no namida

aki ni

namida wa

tokubetsuna

koto da.

Dokutsu wo dettara

~otaku~

seiteki wa

mazaritai

danjyo-jyodan-dandan-jyojyo

hohosometa Amaterasu-oomikami

to okamisama ga kiiro ni narareta ha

no mitai.

Tokubetsuna

koto da.

Aki ni

namida wa

sukoshi amai shi,

kansoushi,

tomerarenai.

Tears in Autumn

In autumn

the tears

are something

special.

If leaving the cave

~home~

gender

wants to mingle

MF FM MM FF

like blushing Lady Amaterasu

and the leaves turned yellow

by her.

Are something

special

in autumn

the tears.

A little bit sweet,

dry,

cannot be stopped.

Commentary

In stanza two, there is a reference to gender and a 'solar disc.' Because Japanese does not assign gender to nouns and does not regularly make use of gender pronouns, it would not be possible to replicate the sense of gender exactly in the case of 'yellowed by her.' Therefore, we have replaced 'solar disc' with a reference to the Japanese goddess Amaterasu, goddess of the sun. This keeps the sun metaphor intact and gives the line a sense of female gender. It has the additional effect of adding a native Japanese element to the poem.

In the same stanza, there is the line 'if they leave the caves,' and 'their home.' Again, because pronouns are not generally used and because the subject 'their' refers to is not defined within the poem, it has been omitted in the Japanese, which can be seen in the back translation.

Sometimes the differences in grammar between the two languages required different word order in sentences, therefore some of the lines have been rearranged. This is not very apparent in the back translation as translated for readability in English instead of a literal translation.

Sarah Uhl + Chris Smiddy

French

Translation

Larmes d’automne

en automne

quelque chose de spécial

sont

les larmes

en sortant de leurs caves

- de chez eux, de chez elles -

les genres veulent

se mélanger

MF FM MM FF

rougeoie le disque solaire

qui jaunit les feuilles

quelque chose de spécial

sont

en automne

les larmes

elles sont douceâtres

sèches

sans fin

Back-translation:

Tears in Autumn

in autumn

something special

are

the tears

upon leaving/going out of their caves/hollows/cellars

-their home-

the genders want

to blend/mix

MF FM MM FF

the solar disc glows fiery red

so the leaves go yellow

something special

are

in autumn

the tears

they are sweetish

dry

endless/never-ending

Marie-Laure Jones and Sally King

Commentary:

Using the pivot language of English, we translated “Tränen im Herbst” from German to French. The lines in the first paragraph required some re-arranging, as their order did not flow in the same way in French as the German version; it made more sense to swap the “are” and “something special”.

The second paragraph had to be cut down from eight lines in the German to seven lines, as with the English, since French grammar does not permit the verb to be at the end, which is required in this “wenn” construction in German, so in the French version, the first and third lines must be joined to be grammatically correct. The construction “if they leave …” was translated using gerund “en sortant …” as it was more idiomatic. “Sortir de” was used rather than “quitter” for “to leave” due to it meaning “leave” in a less permanent sense, which seemed more applicable here. In rendering “caves” into French, there were several options. “Grottes” (tends to be man-made) and “cavernes” (natural) were possibilities, however we chose “caves”, because although less accurate semantically, it seemed most suitable phonetically. Indeed, “grotte” is quite a harsh-sounding word compared to “höhlen”, which would be unsuitable and significantly alter the atmosphere of the poem. Translating “home” raises challenges, as there is no term in French that exactly captures both its emotive and referential aspects. While the feelings conjured up by “foyer” are similar to those of “home”, it is a wider term with more meanings, including “hearth” and “focus”. “Maison”, “habitation” and “chez” are along the lines of “home” or “house”, but without the emotion connected to “home”. We opted for “chez” since it is the shortest in terms of syllables, hence mirrors the source text rhythm most closely.

“MF FM MM FF” could be preserved as in the German and English, as the genders begin with the same letter. As for “to blush”, “rougeoyer” was chosen instead of “rougir”, because even though “blush” used in English is itself more poetic and would be unusual in other circumstances, “rougeoyer” seemed more logical to juxtapose with “the sun”, and both contain “rouge” in the word anyway. “Disque solaire” seemed a slightly odd collocation to us, but “solar disc” is also quite unusual in English, hence it is seemed appropriate to use it here. German quite naturally invents new terms by placing two nouns together, which is less easily done in English or French, so it was not possible to find an exact equivalent. The use of “her” to refer to the sun was problematic, since the French word for “sun” is masculine, whereas in German it is feminine, and in English it is a feminine concept. Omission was used to deal with this, as neither masculine nor feminine would have been satisfactory for different reasons.

To translate “sweetish”, “douceâtre” was used. It can mean “sickly sweet” and “vapid”, among other things, yet the suffix “-âtre” is equivalent to the suffix “-ish”, for instance when used with colours, hence the choice and its suitability here. Use of “never-ending/endless” rather than “unstoppable” is almost like modulation as it is saying essentially the same thing just from different points of view; while “never-ending/endless” considers less the source, but more the stream of tears, “unstoppable” is more from the perspective of the source which then goes on to form the stream. These perhaps reflect differences in approaches in the respective languages.